The Keepers & The Kept

MECKLENBURG COUNTY DETENTION CENTER (MCDC)

Charlotte, NC

Because I didn’t realize that something as foundational as human dignity was so absent in our criminal justice system, I became keenly interested when I saw evidence of it being honored. The Mecklenburg County Detention Center (formerly called the jail) is one of those places. I’d read about the new child-friendly Contact Visiting room for incarcerated folks to visit with their young children and was eager to learn more about it.

What had been only through-the-glass visits before now allowed a toddler to hug and climb on their mom or dad during a visit, and to read books or play with toys once antsy. It was the recently elected progressive sheriff who was the catalyst behind that room – a room with teddy bears painted on the walls and colorful carpet with the ABC’s swirling about.

"I am . . .

a nurturer, optimistic, a mixed child."

As he took me on a tour of the detention center in February of 2020, it became obvious that Sheriff Garry McFadden was more mayor than top brass. Everyone treated him with respect, of course, but there was a warmth and a familial sense, including between him and the residents. In visiting a new behavioral health pod, he was mucking it up with the men about the upcoming Super Bowl.

The sheriff is an impeccable dresser and strikes me as a guy who wouldn’t know how to pull off a casual Friday. And while both his choice of dress and gregarious persona are thrown into stark relief next to bland cinder block walls and the men in orange jumpsuits, he oozes a deep love of humanity. One of his first changes after being elected in 2018 was to eliminate the word “jail” and to refer to the men and women entrusted in his care as residents – not “inmates,” not “offenders.”

This is a man who gives out his cell number and is generous with his Cash app. If a mom emails to check on her incarcerated son or daughter she will have an update by noon, the sheriff told me. He said the residents are in his care and he takes that responsibility seriously. If merely warehousing folks is at one end of the spectrum, the Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office, who runs the detention center, is at the other.

I was pleasantly surprised to learn about all the programming being offered to the residents. Far beyond GED classes, the detention center offers an array of programming in vocational, cognitive, mental health, life skills, and other educational opportunities for its residents. The commitment to instill a culture of dignity alongside detention felt both novel and obvious, and I sensed I wanted to be a part of it.

Dorian

"It breaks my heart to see these women give up on themselves."

When I asked Detention Programs Director, Dorian Johnson, what the biggest need was he didn’t miss a beat in answering: “I’ve been trying to get Toastmasters in here for two years.” But before I taught my first public speaking class there, the pandemic hit and all visitations and programming halted.

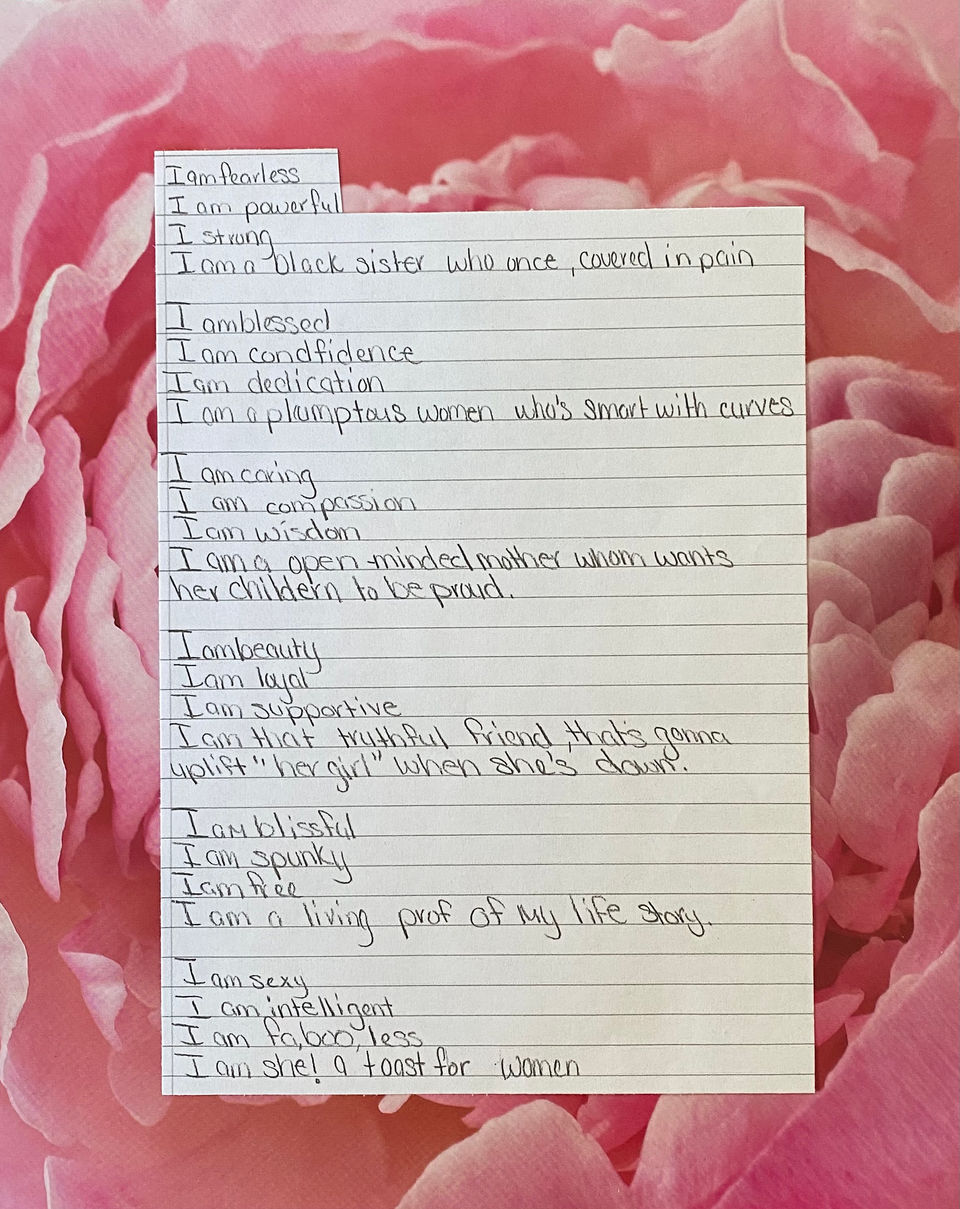

Always looking out for their residents, the detention center started offering some of their programs over Zoom. Dorian asked me to teach the women about vulnerability, courage, shame, and worthiness. He thought Brené Brown's work on these concepts would aid the women in reclaiming their lives, to thrive instead of merely survive their incarceration experience and beyond. Having grown up surrounded by sisters and a strong mother, and as the proud papa of two adult daughters, he has a special place in his heart for the women residents.

“It breaks my heart to see these women give up on themselves,” he said.

He is witness to so much self-loathing in the women, he said. While many put up a strong façade, he’s observed that they crumble at the smallest trigger. There is a hurt in their eyes, their wounds both deeply hidden and just below the surface. Their stories of physical and sexual trauma, the number of women who got caught up in the criminal justice system by way of a boyfriend or husband, he’s gut-sick to hear these firsthand accounts.

“This is who we’re incarcerating,” he laments about the women in his care. “Is this who we need to be targeting with our $80 billion business?” he asked rhetorically of the corrections industry.

“I want the message to be ‘we care about you and want you to succeed,’ and I want to show love,” he said. Dorian said he is intentionally modeling a therapeutic alliance between himself, other staff, and the residents, and that it makes a difference. He said he occasionally gets calls or letters after a resident’s release telling him how useful the programs had been and to offer gratitude for way they were treated.

His message to all the residents: Your worst day (that of the crime committed) is not who you are.

Dorian and the sheriff agree on the primacy of programming, and both view the commitment to treat all the residents with dignity and respect as germane to their rehabilitation and healing. “We are preparing our future neighbors,” is a common refrain from both men.

“I’ve been fighting against the system and breaking the rules all along,” he said of his 24-year tenure in corrections. The “rules” he’s been breaking are well-worn sentiments like; treat people like caged animals, they got what they deserved, criminals don’t matter, they’re here to be punished. Lock ‘em up and throw away the key.

When he first got out of college, Dorian planned to be a corrections officer and went to jail school. The day before he was to start as a CO, he was asked in passing if he was interested in the work release program instead. Never one to prematurely shut down an opportunity, he said, his decision that day changed the trajectory of his life.

Dorian spent 18 years at the Work Release and Restitution Center in Charlotte which allowed residents in custody to work at jobs in the community. His experience there coupled with the progressive and humanizing model that it followed shaped Dorian’s views on incarceration. A mindset he took to his next job as director of adult programs in the county jail.

There is always tension between the detention side of the house and the programs side of the house in any jail or prison, Dorian said. And like most places, the boss sets the tone. He said the current sheriff has placed a more intentional effort to provide and enhance programming, so there are some cultural changes afoot, but it’s an uphill climb because of the overarching paradigm in the corrections world of command and control.

He encourages the officers to try de-escalation, to try speaking with respect, to consider how they’d want their family and friends to be treated if they were inside, but said he’s made precious little progress over the years. “I believe that nine out of 10 times, or eight out of 10 times if you’re a pessimist, de-escalation attempts coupled with calm communication works,” he said. Dorian said he’d welcome the opportunity to explain why his approach is better, but he seldom gets challenged on it. Yet he remains hopeful that a shift to a more dignity-centric culture is possible, if glacially slow.

Corrections officers in the programming pods must apply for the position, and Dorian said that officers who lean more punitively aren’t interested. What seems like a better post, theoretically a cushier position, is in fact harder work because you must be relational with the residents. For that majority of CO's who desire power over instead of power with, the position is of little interest.

Dorian is an understated man with a calming presence. His fund of knowledge is vast, both in facts and figures, and in the language of helping people. He is a patient, loyal, one-foot-in-front-of-the-other kind of guy. He speaks with very little voice inflection and has a serious poker face. From his days as a screening manager, he told me when I asked.

Dorian said that many of the residents are so lost they don’t even know they’re lost. He says he knows that feeling from his youth in Buffalo, NY. And while he never got mixed up in crime, he said it could have just as easily happened to him. “At work, I feel like I’m saving people like me, people I grew up with,” he said.

His gratitude for how his life turned out is palpable, and he said that his job offers a steady reminder. “Every day I get to see what could have been my life… For whatever reason, God saved me.”

He’s helped several residents over the years and said he has never been “burned” by any of them, taking issue with my use of the word in my question. He readily admits their path to making good choices is seldom linear, but he believes he has good instincts about who and how much to help and feels equipped to distinguish between helping and enabling. “Using wisdom, I will always try to help someone,” he said.

Heather

"Sitting in this nine by six cell, which by the way, equals 54 square feet of hell . . ."

I first became acquainted with Heather through some of the classes I taught at the detention center over Zoom. I noticed her in the group early on. Slid down in her seat with arms crossed, she looked like she’d rather be anywhere else. I saw what appeared to be an emotionless face even through the gauzy screen and her surgical mask. Thankfully, I knew better than to try and play to the one person in the room who you think hates you.

Ultimately, she was an engaged participant in the writing classes and quick to share with her fellow classmates. I tried hard not to shine too bright a light on her natural talent, but I’m sure my body language and choice of words betrayed me each time she read her work. Who, sitting in a jail cell, is weaving Poe and Hemingway, both the men and their works, into the poetry they are writing?

I offered one-on-one help to anyone who wanted it and she was the only one who took me up on it. We spoke a handful of times over several months. She sent me handwritten poems and stories for feedback, sometimes via email through detention center staff and several times by mail directly to my home.

During one of our Zoom calls, she had to go fetch a piece of writing she’d left behind in her cell. As she turned to leave the room, her long black hair swished over PROPERTY OF MCSO stamped on the back of her burgundy scrubs uniform.

I asked her if she was willing to be interviewed for an essay I was writing about female incarceration, and she readily agreed. She told me that while she was not a huge criminal justice reform person, she believed deeply that jails and prisons needed to practice more humanity towards their residents. Describing the culture, she said guards tended to talk down to the women, “like we’re kids … like we’re inferior.” It creates a mindset of hostility to be treated like a child, she said.

She said she made a conscious decision to better herself and be productive with her time while inside, and said she preserves her dignity and humanity by reading self-help books. Heather recently read The Four Agreements and tries to remember the teachings when she gets offended. (Agreement #2: “Don’t take anything personally.”)

Heather strikes me as an introspective person, even if that’s the incarcerated version of her. Her writing reveals a person who seems well acquainted with her shadow side, and wrestles with it mightily: When I write stories, I feel like my life is as frayed and tragic as Hemingway.

She frets about getting a job and making clean money when she’s out. She said she’s worried about squelching her criminal mindset – it’s hard when you know how easy it is to wake up broke and have $10k by the end of the day – but she knows she simply must. Not just for her kids but for herself. If she were to ever be involved in crime again, she said, she’d be looking at 15-20 years: I swear I will not go back to my old lifestyle “Quoth the Raven, ‘Nevermore.’”

She spoke about the ugly reality of being in a controlled environment and being solely reliant on others, especially guards. Always having been so independent, she posits it’s especially hard for someone like her. “I didn’t need anybody,” she said recalling her self-sufficiency on the outside. Now she’s forced to press a call button to alert the guard she needs to use the restroom if the urge strikes overnight. Single room with a window and a door, yes. Individual toilet, no: Sitting in this nine by six cell, which by the way, equals 54 square feet of hell, I have learned what it means To Have and Have Not.

A college graduate, Heather muses about the possibility of vet school one day. And being able to see her sons again. She admits her boys suffered a chaotic childhood, including time spent in foster care, yet her eldest son recently accepted a full ride to a competitive public university. “He’s beat all the odds,” she said. Her tone is flat, as is typical, but I assume there is deep pride inside.

Heather was eager to have her work published and assured me she was not looking for notoriety or income. I mentioned that a local podcast for readers and writers might be willing to publish something on their blog if she was interested in my submitting on her behalf. She was as enthusiastic at the prospect as anytime I had seen her. Part of the essay she submitted included:

“Writing has led me down a liberating path of self-discovery and afforded me the opportunity to seek forgiveness from others, and also to forgive myself. And nowhere do I seek more atonement than from my teenage sons."

Read her entire story, “The Pencil Chronicles,” recently published on Charlotte Readers Podcast’s community voices blog.

Portraiture

Your boyfriend teaches you how to sell drugs and you’re surprised by how easy it all is. And while oxy is your favorite, you learn that meth sells best.

You keep the books, and he works the streets. A 1950’s-style marriage, a delineation of labor, both playing to your strengths. Your weakness: watches and purses. His: BMW’s and guns. Friday night is girls’ night when you and your BFF go to the mall. First stop, Michael Kors.

Your first arrest is for meth: Possession. You are 22. You serve seven months between two facilities. You don’t get any drug counseling in either place because you aren’t there long enough. At least that’s what they tell you.

Your second arrest, now 31: Possession, conspiracy, plan to distribute. This time you’re looking at 87 months. You could have turned him in, saved yourself quite a bit of trouble. Clearly that’s what the cops were hinting at when they told you “Just tell us it’s him and we’ll let you go.”

You are parked in jail until you are sentenced. You have a small window in your jail cell which resembles a cramped dorm room devoid of any color or character. You watched the Black Lives Matter protesters that summer with tears in your eyes. From your window you’ve watched the leaves change from green to brown and falling, and back to green again.

You miss life outside: shopping with your grandmother; Hibachi chicken and a Sun Drop for lunch; lying on the couch in comfy clothes, wrapped up in a blanket watching television.

You don’t talk to your old friends in the free world as much anymore. With 56 women vying for six payphones, you no longer waste time and money on friends who sound high every time you call. Your tether to the outside world is slipping.

You fantasize about how much freedom there will be in your new prison home, the one you hope you get assigned to. Your attorney gave you the handbook to read. It won’t be as strict there, you say. There will be fresh air, exercise, and a prison campus to walk around in real sneakers. “There’s sunshine in prison,” you say.

You already fret about your release, returning to your mama’s house one day, what with her meth-addicted boyfriend and all. You worry about that environment and her permissiveness. What if you start using again? You could never pull the wool over your daddy’s eyes. He has no time for your drug use and other shenanigans, and always seems to know when you’re high.

Your mama writes you often and pretends you’re off at college. You send all your “Certificates of Completion” home to your daddy. He’s proud of you, but you know you are only slowly gaining back his trust.

You spend your days mostly locked down in your cell because of COVID. Programs are canceled (again) so your days are filled with Nicholas Sparks and Kristin Hannah (again). Maybe re-reading a letter from your mama. The idleness feels like a straitjacket.

You especially love practicing for the debate, researching the questions, working on your presentation skills. You get to dress up and be a real person for an hour and present to an audience over Zoom. You feel accomplished and empowered and forget for a moment that you are property of the Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office.

(With gratitude to Brooke, for sharing her story with me.)